Building systems change initiatives into practice

Lead for Systemic Change

This blog is the first in our series on systems thinking. In this blog we explore one of the systems dynamics tools we use called goal-gap structures to help us understand people’s different motivations for change. We will be launching a systems training programme this autumn where you can learn more about these approaches!

At Dartington, we use systems thinking to help us understand the different actors in a system and their motivations for change. Whilst there is important knowledge and evidence in the way services understand and define need, we have found that it is important to widen our lens so that we can see needs, goals, motivations for change from different perspectives.

In this blog, we share one of the tools we use to understand motivations for change. This tool is called a goal-gap structure and it is a foundation of system dynamics approaches.

Goal-gap structures highlight the observable behaviours which actors in a system exhibit to reach their goal. Understanding the goals that people have, and the ways they go about reaching these goals helps explain the relationships that people have within a system, and some of the conflicts that can arise about how they work together. This understanding is particularly important when it comes to systems of support for young people. Sometimes services and supports are poorly designed for what young people need. Even with the best intentions, there can sometimes be a lack of clarity about how to ‘re-design’ these services to better meet a young person’s own way of realising their goal.

For our systems change work at the Lab, we’ve been developing an approach using goal-gap structures to understand stakeholders’ motivations, actions, and their impacts. This is a great tool for service design or even evaluations as well as systems change projects.

Earlier this year, we ran a kick off workshop to launch the Systems Thinking and System Change Modular learning platform we developed with Barnardo’s. One of the activities we did was called Interaction Loops. These interaction loops use goal-gap structures for stakeholders who interact with young people, schools, statutory services, third sector, their families, peers, and communities. Below, we explain how this exercise worked, what we learnt and how Barnardo’s are leading the way among service providers for thinking about the importance of the systems around them and building systems change initiatives.

Understanding the relationship between goals and actions

The Interaction Loop has four components connected in a balancing loop - that is factors that through their causal connections reach a balanced equilibrium:

1. The observation

2. The objective

3. The action

4. The impact

To illustrate, imagine a counselling service acting as an intervention for the experience of depression. The observation there is depression, and the objective is good mental health. The observation there is a young person experiencing depression and the objective is good mental health. The gap between these two is what motivates the intervention and prompts the action of the counselling service. If there wasn’t a gap, then there wouldn’t be any motivation to act and having a larger gap should prompt a bigger action (think of intensive services for acute depression).

This counselling has an impact through which it improves the outcome and brings it closer in alignment to the objective. In the example, we might expect counselling to be the mechanism that works in closing this gap, assuming that a core part of counselling might be around identifying and responding to emotions and help to close the gap between depression and good wellbeing.

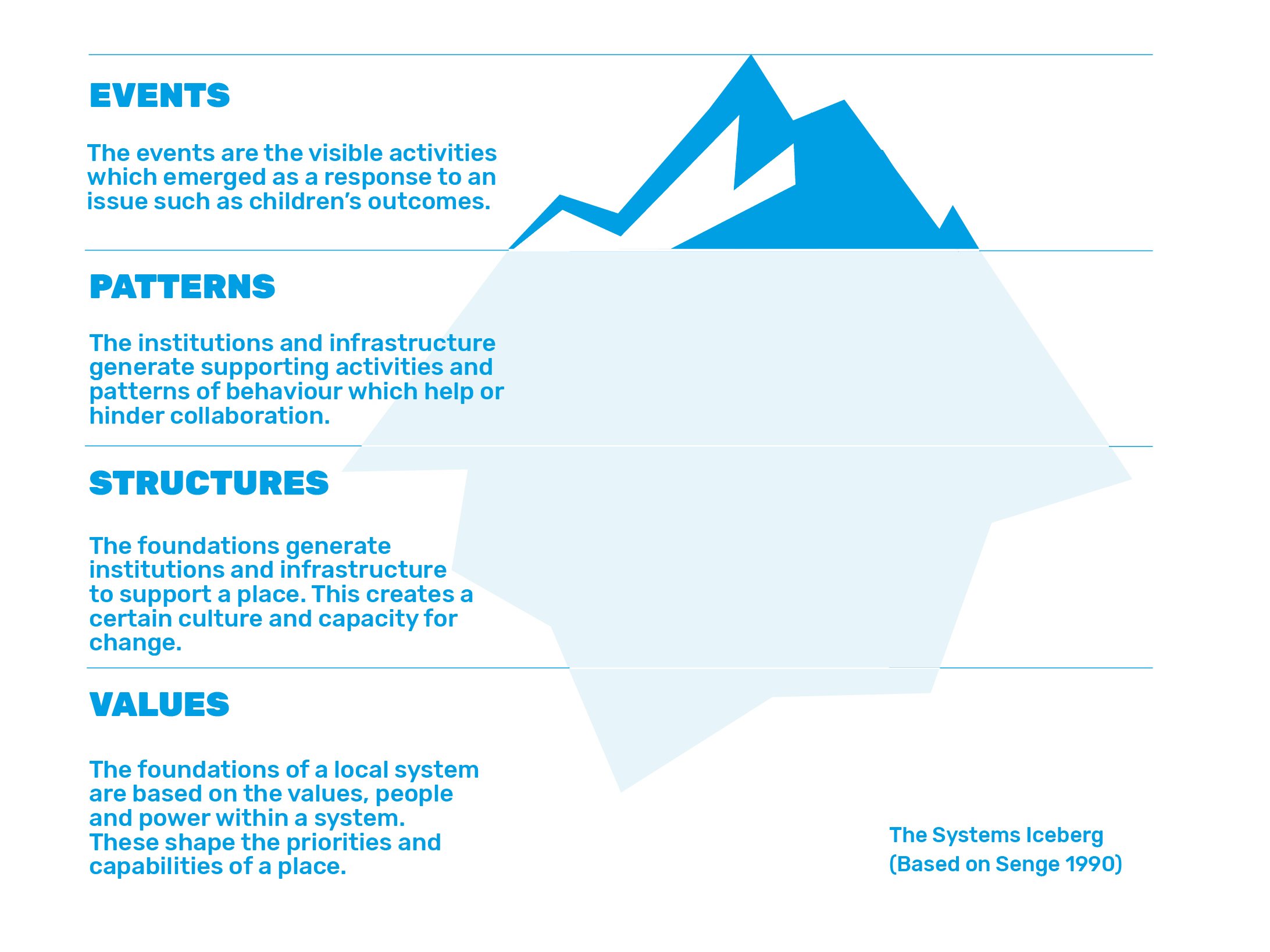

The difficulty often comes when we think about people we’re working with who have objectives that are different from ours. Sometimes we people take actions that have a negative impact on our objectives and it surprises us, or brings us into conflict. This is where the Interaction loops activity comes in! Where the activity can be helpful, is to make sure we are clear on why people in a system are doing what they are doing and why it might be different from our approach. In our workshops, we use systems thinking iceberg to help us examine the goals and underlying beliefs and mental models which lead people to adopt their specific goals, so that we can see where there might be underlying agreements (or differences) in the beliefs and assumptions we have about how to best support children and young people.

Understanding different perspectives: How identifying different goals helps us find ways to align services to user needs

In the workshop with Barnardo’s, the participants found the activity productively challenging. One group were building a model around the systemic problem of services not capturing young people’s voices. The stakeholder they focussed on was the young people themselves. They started with the outcome of having a service which suits young people, and the objective of having young people’s voices captured in service design. The action; that young people take is to avoid services that don’t suit them. The impact of not attending a service for young people is they then have more free time, since they weren’t spending time in the service. The issue in this example is this doesn’t close the loop. The action of not attending a service does not bring young people closer to Barnardo’s goal of having services which reflect young people’s voices.

In this case, the team from Barnardo’s were thinking about their own goal rather than the young person’s goal. With guidance, they were able to step back and identify the young person’s objective and their observation – what the young person was seeing that motivated them to act. The Barnardo’s team were bringing a deep understanding of young people and what causes them to disengage but weren’t clear on what might be the goal for young people. In the workshop, the team were able to step back and identify the young person’s objective and their observation – what the young person was seeing that motivated them to act. They saw that the objective was better framed as spending time with a service that doesn’t suit them; and that their objective is around understanding a meaningful use of their time.

Final thoughts: The value of challenging our assumptions and why we use systems tools to do that!

The value of this kind of modelling is that we can develop learning around knowing and challenging assumptions around what drives people to take action. This is particularly important when working with young people who are often underrepresented in the service design process. This activity can also serve as a springboard for deeper thinking about why stakeholders’ actions are often limited in their impact, have unintended consequences, or conflict with their own or others’ larger goals. Barnardos’ staff want to work with young people to design services that are meaningful for them. In the workshop, they shared reflections about how the young people who don’t attend services, often see their outcomes worsen or fail to improve. In our workshop with Barnardo’s, they showed a deep commitment to understanding why services struggle to facilitate engagement in co-design with young people and reiterated their commitment to as a result there are few opportunities for involvement in decision-making to support shaping services to meet young people’s goals. Our collective conclusion is that meaningful participation of young people will ensure everyone’s goals are met and listened to, further contributing to improving outcomes for children young people and families.

To find out more about our systems change work and partnership with Barnardo’s please contact; Megan Keenan. To learn more about our systems training, please contact Leanne Freeman. You can also visit our website to sign up to attend our systems training.